Galleon from Scrap

Before even completing Artesania Latina's re-release Baltimore Clipper Harvey (AL22416), I knew I would have no choice but to directly continue to another wooden ship model. Unfortunately, during the eight months I spent assembling her, the market for such kits seemed to dry up completely. The website from which I purchased her no longer seemed to carry any wooden ship kits, and the offerings from other sites are beyond my budget and size restrictions.

Before even completing Artesania Latina's re-release Baltimore Clipper Harvey (AL22416), I knew I would have no choice but to directly continue to another wooden ship model. Unfortunately, during the eight months I spent assembling her, the market for such kits seemed to dry up completely. The website from which I purchased her no longer seemed to carry any wooden ship kits, and the offerings from other sites are beyond my budget and size restrictions.My goal of advancing in difficulty and consequently, price, through each additional model came to a halt during my search for the next project. Harvey marked my second attempt at wooden ship building. Prior to her, Swift 1805 (AL22110) gave me an introduction to plank on plank* construction methods, but I much preferred the plank on bulkhead* method of hull construction taught to me by my experience with the Harvey. Swift cost me about $75, and the $150 Harvey I got for a steal at $100 shipped. The next step should have brought me to the $300 level whose price perhaps could have been justified by the second quality that subsequently disqualified it: size. Both the Swift and the Harvey measure around two feet in both length and height, leaving mantle mounting an option, but the more expensive kits double in both price and size quite easily. A three to four foot long ship requires its own display table and quickly reduces the usable size of my 3'x6' hobby table during assembly.

As an individual whose 1995-1999 college tuition money would have served better me had it instead been invested in Amazon, Yahoo, or Google, as I would never have lifted another finger in my life for the purpose of earning money, I of course turned to the internet for answers. Model plans existed here and there for purchase, but reluctance to purchase them came quickly without example pages or images of completed models. Further searches revealed links to military sites for actual plans of actual ships, but I felt that translating these into modeling terms might be beyond my capability. Also, I didn't feel ready to advance into the navies of the 20th century. Finally, after dismissing plans for small ships intended for full scale building (I'm not that near to water), I happed upon a personal webpage offering encyclopedic type drawings for free. Quickly I realized that if I could adjust the scale properly, the scrap wood left over from my previous two ships along with the wood I'd saved from my high school days of balsa airplane construction might just be enough to build a third ship for almost no cost!

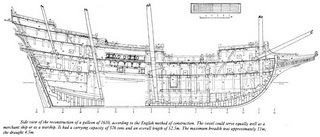

My main obsticle to just creating something from scratch has always been hull design. During college I made a few ships using only cardboard, again keeping with that no budget mentality. I really needed some concrete plans from somewhere with wood construction being much less forgiving than cardboard. The selection of ship plans I'd found varied from whalers to strange Dutch vessels, but I chose what I felt to be the simplest in terms of geometry to create from a few pictures downloaded off the internet: an early 17th century English galleon. Only the ornamenture and level of rigging I decided to pursure could slow my progress. Though the intent of the images was clearly to print them map sized, I felt the level of detail produced from my 8.5"x11" inkjet should be a sufficient start. After studying the seven images associated with the Galleon and determined to take over my life for the next year possibly, I came to the conclusion that I would have just enough wood to produce the ship at a 1:100 scale. Good news: the completed galleon's size should be similar to that of my other two ships. Bad news: the other two ships are scaled to around 1:50, so I needed to split the majority of this thin, remaining planking in half somehow.

Galleon model detail

Well, from the title picture I've come a long way but still have much to do. This blog will be updated with future advances as I feel necessary. Feel free to contact me with any questions.

*Basically, plank on plank resembles paper mache since it consists of applying multiple layers of extremely thin plies of wood to the bulkheads. This gives you two chances to cover the hull completely and properly: one to define the shape and another to lay down a better quality but equally thin layer of wood which should cover all surfaces perfectly and without gaps. Plank on bulkhead differs by using single, thicker strips of wood to cover the bulkheads. This method offers three dimensional shapes to cover a three dimensional surface and leaves the majority of errors to be eliminated via sanding. The thin layers of plank on plank really only serve as two dimensional shapes and can really have problems bending in too many directions. Plus, forget about sanding due to the shear thickness (or lack of) of these plank on plank members. Any material removal beyond exposing a virgin layer for varnishing cuts right through the layer and exposes the lower levels assuming any exist and leaves gaps if no lower revealed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home